History of Olympic Weightlifting

Site Sponsors

The Lift Up project is brought to you by chidlovski.com.

The Lift Up project is brought to you by chidlovski.com.

Olympic Legends @ Lift Up

Lift Up Site Search

Home ›› Feature Articles ››

Feature Articles @Lift Up

Norbert Schemansky

by Jerry Green, The Detroit News, January 2002

DEARBORN - One day 50 years ago Norbert Schemansky asked his boss for some time off so that he could participate in the Olympics.

The boss shook his head and said no.

"I was working at Briggs Manufacturing and I asked for time off, and one of the guys from downstairs said, 'Give him all the time off he wants -- fire him,'" Schemansky said.

"I said, 'Bleep you, I'm leaving.'"

This is one of Schemansky's stinging memories that linger a half-century later. He went on to those 1952 Olympics in Helsinki and beat his Soviet rivals and won a gold medal. Then he came home to the United States and to Michigan and returned to obscurity.

Schemansky was a weightlifter, a world-champion heavyweight, and weightlifters in America do not receive their deserved acclaim.

Now 77 with bum legs and an aching back, he sat in his home of 43 years on the west side of Dearborn last week and discussed his experiences as an athlete who was renowned around the world, but not at home. Schemansky is better known in Moscow than he is in Michigan.

As another Olympiad is soon to begin, Schemansky could be called one of the last pure amateurs.

He won four Olympic medals -- the gold, a silver and two bronzes in four Olympiads from 1948 to 1964 -- and a bevy of other junk, as he calls it, in various lifting competitions.

"Not a penny," he said about his earnings as a competitor.

Today's Olympians are well-paid professionals, many multimillionaires. Fifty years ago, Olympic champions were forced to struggle and look at their collection of medals.

"Would you believe somebody competed for something like that?," he said.

He displayed a tarnished medal smaller than a thumbnail.

"There aren't any more Olympics," Schemansky said. "They're the money games.

"There's no more real Olympic spirit. I was looking at a picture of a kid skiing in Sports Illustrated. He's got 13 endorsements. His headband's got a name on it. The poles got a name on it. The skis got a name on it. His laces got a name on it."

Schemansky never got an endorsement.

"You couldn't take anything," he said.

Today's Olympic competitors beef up on special diets prepared by dieticians, and many feed on supplements, some on steroids.

Schemansky had his special diet, too, when he captured the Olympic silver in London in 1948, his gold in 1952, and his bronze medals in Rome in 1960 and Tokyo in 1964.

"Hamburgers. Pizza. Beer," he said.

"If I was competing now, I'd be a millionaire. Budweiser'd sponsor me. A hamburger joint. Mike Ilitch."

In weightlifting circles, Schemansky is regarded as one of the greatest in the sport's history.

"In New York and in Moscow, in dimly lit cellar gyms and plush training centers, in camps of friends and foes, in 2066 and 3066, the story of Schemansky -- already a legend in his own time -- will be told," Joe Weider, a noted trainer, wrote in an article in a weightlifting magazine.

Through the years while Schemansky was competing -- and failing to receive funds or recognition -- his target was the Amateur Athletic Union. The AAU controlled the United States' Olympic athletes then and the rules were strict.

Once Schemansky was headed toward a competition and the AAU gave him a patch to sew onto his jacket over his heart. He stuffed it into his back pocket.

"That's where it belonged," he said. "They didn't like what I used to tell them."

RISE TO TOP

Schemansky started weightlifting in a makeshift gym on the east side of Detroit in the 1930s, before World War II.

"My older brother was a weightlifter," he said. "He was a national champion. I was 13 or 14 and I'd hang out around the gym.

"The gym was a converted two-car garage. Within a couple of years, I was doing more than the guys that were training for years in there.

"The gym was on Gratiot and McClellan," he said, "Right now the expressway runs right through there."

While a student at Northeastern High School, his other sport was track and field.

"The shot put," he said. "The coach looked at me -- I only weighed about 160 pounds then, the other kids were close to 200 -- I kept beating those guys. I made All-City.

"You know about the technique? He said go across the street to the backstop, the baseball field, and throw the ball over the backstop.

"That's the only coaching you got then."

In the early 1940s, Schemansky went off to war. He was attached to an anti-aircraft unit in Europe. He fought in the Battle of the Bulge when the Germans tried a counterattack in December 1944.

"We got 30 planes and 360 buzz bombs," Schemansky said of his military service.

It was in the Army that Schemansky earned his first medals -- five of them for meritorious service.

After the war he resumed his career, competing, working, marrying, raising a family -- being snubbed and threatened with being fired.

"I had jobs on and off and my wife worked a lot -- if it weren't for her I probably couldn't have done it," Schemansky said. "Bernice. She's gone six years now."

Schemansky already was a world champion before he went to Finland for the 1952 Olympics, jobless and proud. And in Helsinki he accomplished what no weightlifter had ever done before.

"I was the first heavyweight to lift double-body weight," he said, "When I won the Gold Medal I weighed 194, 195, and I did 399.

"To make weight then, we'd just clean our nails, clean our toes, spit."

OBSCURITY AND ACCLAIM

The lifting damaged Schemansky's body.

He twice ruptured a disc, had operations and resumed breaking world records. He defied his doctors.

"The doctors said I'd never walk," he said. "Maybe they were right. I'm not walking good now.

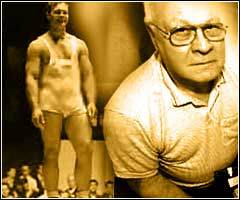

"See that picture? That's over 400 pounds; I'm getting up on one leg. Right now I can't get up on that leg with no weight."

But even then, before Michael Jordan and Steve Yzerman and Dominik Hasek became Olympians, amateurs such as Cassius Clay, before he became Muhammad Ali, were revered for winning gold medals. But weightlifters were ignored, and Schemansky offers a reason:

"You didn't have television. Now a lot of people know about weightlifting and bodybuilding. They see stuff on television.

"If you walked around with a gym bag then, they said you were nuts. Now everybody's nuts."

Even so, he remains better known today in Russia than in America.

"I got more publicity there than here," Schemansky said. "A friend of mine used to go to Russia every summer, and he was sitting in restaurant and he was talking about me, and the waiter overheard him mention my name and the waiter wanted his autograph because he knew me."

Schemansky had a wistful look, glancing at the interviewer.

"Is there anything here on the upbeat? he asked. "Everything seems like it's knocking stuff."

"I got a park named after me in Dearborn," he said, showing a photo of Schemansky Park. "That's an upbeat thing.

"People were asking, 'Who was Schemansky?' So now they put a plaque down here with my achievements."

Gallery

Videos and Gallery of Norbert Schemansky is available in his section of the Hall of Fame @ Lift Up.

Comments? Questions? Memories?

Back to Feature Articles